As the world approaches the Beijing+30 anniversary, and with the 2025 High-Level Political Forum just ahead, it’s time to confront how economic policies are entrenching gender injustice. From rising wealth inequality to gender-blind macroeconomic models, CESR’s Marianna Leite argues that the review of SDG5 must go beyond rhetoric. Only structural change and rights-based accountability can chart a path toward gender-equal futures.

By Marianna Leite, CESR's Director of Program

The world’s richest 1% own 43% of all global financial assets, according to Oxfam’s 2025 Inequality Report. Since 2020, the five richest men doubled their fortunes, while almost five billion people have seen their wealth fall. Oxfam calculates that it would take 1,200 years for a female worker in the health and social sector to earn what a CEO in the biggest Fortune 100 companies earns on average in one year. This is not only unfair and unjust, it is immoral. Globally, men own US$105 trillion more wealth than women – the difference in wealth being equivalent to more than four times the size of the US economy. At current rates, it will take 230 years to end poverty, not five as determined by Agenda 2030. As we approach the upcoming review of Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG5) on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment, we must constructively look at how the current macroeconomic model and related policies are failing women globally.

Decoding gender injustice in macroeconomic policies

The 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BPfA) provided an improved and strategic framework whereby women’s rights were placed front and center. Agreed by 189 governments at the Fourth World Conference on Women, the Platform identified 12 priority areas for changing the situation of the world’s women, establishing the methods by which all actors are to eradicate the persistent and increasing burdens of gender discrimination and poverty on women by addressing its structural causes, ensuring equal rights for all.

The BPfA recognized the crucial role of macroeconomic policies in advancing women’s rights and gender equality, emphasizing that these policies must be designed and implemented to address structural causes of poverty and gender inequality. The BPfA called for incorporating gender perspectives into macroeconomic policies and programs, including taxation, international financial institutions, and lending programs. Despite the potential of this transformative framework, we are still far from reaching equality at all levels.

In the recently launched Decoding Gender Injustice report, CESR explains that the current macroeconomic structure is gender-blind. It does not value care work and it is underpinned by colonial, patriarchal and neoliberal legacies. For example, the global economic system exploits care labor by requiring its free or underpaid provisioning in order to reproduce the labor force without adequately recognizing or rewarding it. Care is not only a right but a public good without which the real economy and labor market cannot exist. Recognition of the care economy requires compensation of care work as well as dismantling the structures of inequality that reinforce the unjust existing care economy.

Going beyond the Beijing Platform for Action in the review of SDG5

The theme of the 2025 High Level Political Forum (HLPF) is “Advancing sustainable, inclusive, science- and evidence-based solutions for the 2030 Agenda and its SDGs for leaving no one behind”. Every year, HLPF zooms into specific goals to measure their implementation and propose ways to ensure the achievement of the joint commitments made by Member States through Agenda 2030. The 2025 HLPF will have an in-depth review of Sustainable Development Goals 3 – Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, 5 – Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, 8 – Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all, 14 – Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development, and 17 – Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development.

In preparation for the review of SDG 5, the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA) and UN Women organised together an Expert Group Meeting (EGM) on SDG 5 and its interlinkages with other SDGs. The SDG5 EGM summary report states that ‘with just five years remaining until the 2030 deadline for achieving the SDGs, gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is off track’. This is an understatement. When SDG 5 was last reviewed at the HLPF in 2022, core issues were highlighted ‘such as the immense burdens women faced during the COVID-19 pandemic, including loss of employment, increased gender-based violence, and disruptions to health services’. While there have been positive developments, most of these issues persist. Moreover, implementation of SDG5 continues to be patchy and uneven across regions with a considerable amount of setbacks as a result of fierce backlashes against gender equality and women’s rights. For example, “parity in women’s participation in public life remains elusive, and at the current pace of progress, achieving parity in management positions, is projected to take an additional 176 years, instead of 5 years as prescribed by SDG targets 5.1 and 5.5”.

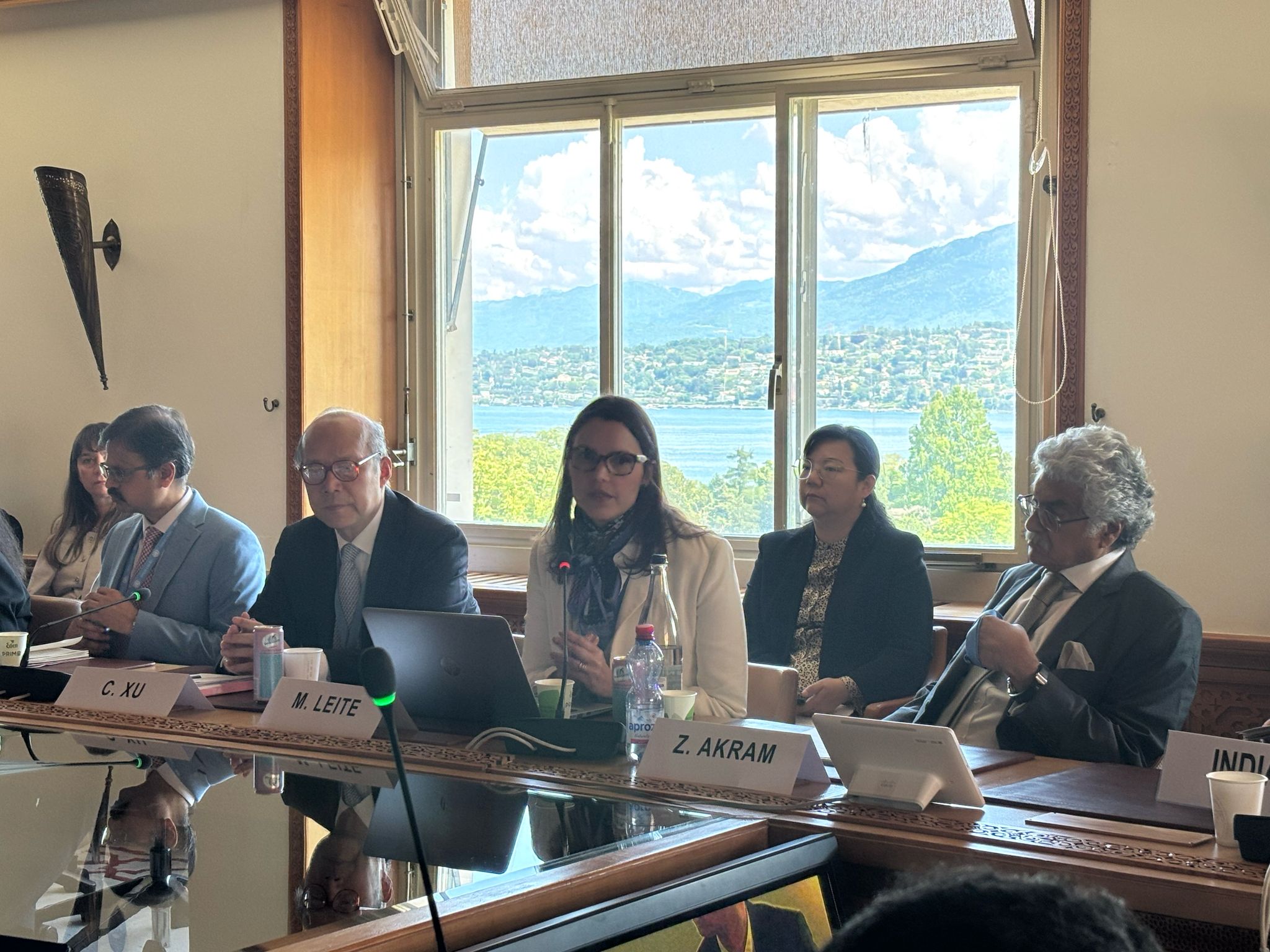

CESR’s reflection of CSW69 underscored the fact that although BPfA galvanized momentum around the globe, its core commitments have always been political rather than legally binding, meaning that each government’s implementation depends heavily on national priorities and available resources. As noted during the Beijing +30 side event co-sponsored by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Development and the Permanent Mission of China that took place in Geneva on the 14th of May 2025: “Beijing is the bare minimum. Without binding rules, public financing, and human rights accountability, it risks becoming a ceiling—not a springboard.” The message heard from the Member States that were present in the room - namely Singapore, Denmark, Mexico, India, Pakistan, Germany, Venezuela, Maldives, Ethiopia, Cyprus, Belarus, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Hungary and Honduras - was one of renewed commitment to BPfA and its links to SDG5, yet the level of ambition could be increased.

Charting gender equal futures

Currently, women are still being prescribed a lifetime of hardship and duress as they navigate the barriers imposed by patriarchy, neoliberalism and (neo)colonialism. This is increased by intersectional inequalities such as race, age, ability and national origin. But this does not need to be the case.

On the 16th of July, from 13:15 to 14:30, at UN Conference Room F, we will continue the conversation started at CSW69 and in Geneva at a HLPF side event co-organised with the mandate of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Development and co-sponsored by the Permanent Mission of Germany and the Permanent Mission of Brazil to the UN in New York.

During the event, CESR will stress that the review of SDG5 can be used to build on the momentum created by CSW69 on Beijing+30 as well as by 4th UN Conference on Financing for Development Conference (FfD4). Equally so, the HLPF space can serve to further mobilise a coalition of the willing towards the timely and efficient delivery of the concrete targets under SDG5. This, in our expert opinion, must be done both through the implementation of legally binding instruments such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and related General Comments. This means that Member States must ensure that women, in all their diversity, can meet their full potential by ensuring not only equal opportunities but also gender-equal outcomes. It implies altering macroeconomic policies to ensure that the global economic prescriptions enable gender equal futures rather than a hindrance to it.