CSOs (including our Executive Director, María Ron Balsera) and UN delegates. Photo via Latindadd.

CSOs (including our Executive Director, María Ron Balsera) and UN delegates. Photo via Latindadd.

Last November, governments gathered in Nairobi for the third session of negotiations on what is poised to become the world’s first UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation. For the first time, the deliberations moved away from New York and took place on the African continent: a shift that carried both symbolic and substantive significance. Nairobi brought into sharper focus the underlying political choices that will determine whether the new Convention can advance equality, expand fiscal space, and strengthen the public systems people rely on.

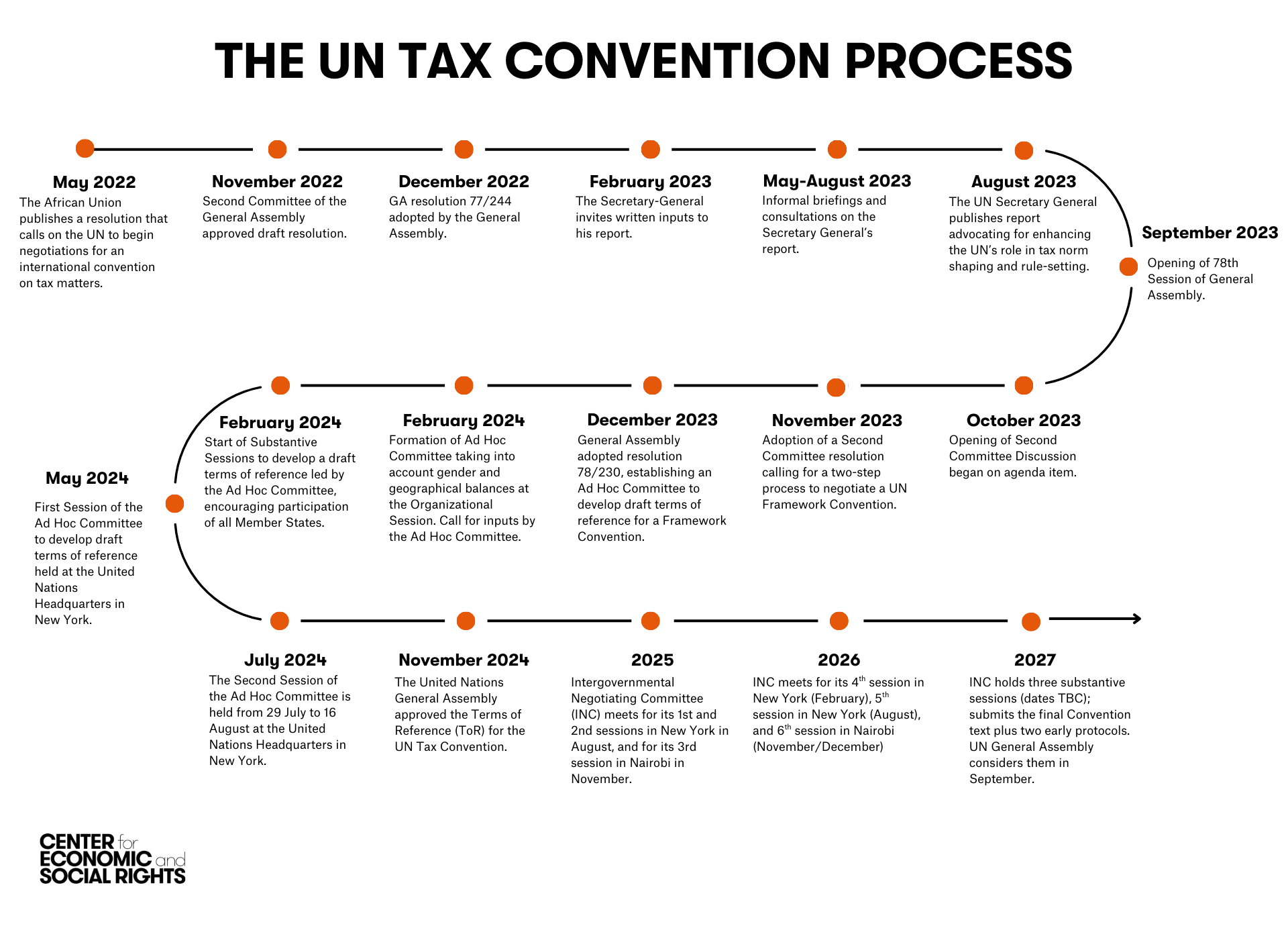

This third session built on the mandate given by the UN General Assembly in 2024, when States adopted the Terms of Reference for a global tax cooperation framework, in a resolution tabled by Nigeria on behalf of the Africa Group. The formal process started with an organizational session, held in February 2025, and two prior Intergovernmental Negotiating Sessions held in New York last August. This process is a win by civil society from all over the world, who have worked for decades to link global taxation to human rights and achieve fiscal justice. Additional sessions will be held through 2026 and 2027 to finalize the Convention and its initial protocols.

Find out more about the UNTC process in our Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs).

In Nairobi, delegates worked through the zero draft (a “template”) of the Framework Convention and The co-leads full draft of the Protocol on Tax Dispute Prevention and Resolution.

CESR, who has been present in the three negotiation sessions, provided daily summaries. The negotiations highlighted both progress and deep divisions, with disagreements concentrated around taxing rights, transparency, capacity building, taxation of rich or high-net-worth individuals, and the purpose and scope of dispute resolution.

A political debate, not a technical exercise

Over twelve days, negotiators confronted questions that go to the heart of global economic governance: Who gets to tax? Who gets access to information? Who must adjust their national policies, and who retains policy space?

Discussions on capacity building, allocation of taxing rights, dispute settlement, and sustainable development revealed sharply contrasting visions for what global tax cooperation should achieve.

Capacity building: a question of power

Many countries (including Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Zambia, Colombia, Bangladesh and Small Island Developing States, such as the Bahamas or Jamaica) insisted that capacity building must be country-driven, long-term, institution-strengthening, and aligned with their domestic priorities. They emphasized the need for:

-

Automatic access to tax data.

-

Digital infrastructure.

-

Sustainable financing.

-

Regional centres of excellence reflecting local realities.

Other States favoured narrower, short-term technical training. The split raised a fundamental question: Will capacity building level the playing field, or reinforce existing hierarchies?

Dispute resolution: warning from experience

The debate around dispute settlement was animated by global experience with investor-state arbitration (ISDS). Countries including Nigeria, India, and Zambia opposed introducing arbitration into the tax field, warning that it could mirror existing systems where tribunals award hundreds of millions (even billions) based on projected (not actual) corporate profits. Such awards drain public coffers, constrain social spending and available resources to fund education, health and other human rights obligations.

Voluntary mechanisms such as joint audits gained broad support, but the introduction of “optional” arbitration raised concerns given the way optional mechanisms often become de facto mandatory in bilateral negotiations.

Sustainable development: still too thin

Discussion on sustainable development was perhaps one of the most forward-looking aspects of the third session, but the draft articles remained broad and high-level. Negotiators acknowledged that tax rules shape governments’ ability to:

-

Strengthen social protection.

-

Respond to climate impacts.

-

Reduce inequality.

-

Fulfil economic, social, and cultural rights.

Yet the draft text did not yet embed these obligations in meaningful or actionable ways. Nairobi showed that tax cooperation cannot be siloed from human rights, climate justice, gender equality, or development goals. Unlike negotiations at the OECD, development and human rights (together with peace and security and the rule of law) are pillars of the UN, therefore, the UN Framework Tax Convention must be aligned with these commitments.

Integrating key civil society proposals

Although many of the negotiators' interventions lacked ambition, several proposals from civil society gained some traction during discussions:

1. Transparency and reporting

-

Public country-by-country reporting

-

Strong rules for automatic exchange of information

-

Requirements for beneficial ownership transparency

These measures would enable governments, particularly in low-income countries, to detect profit shifting and enforce tax laws.

2. Fair allocation of taxing rights

Proposals emphasised taxing rights based on economic presence, sales, and user participation — rather than narrowly defined “value creation” principles that tend to favour residence countries.

3. Minimum standards and anti-abuse

Civil society highlighted the need for coordinated rules on:

-

Global minimum taxes

-

Exit taxes

-

Taxation of high-net-worth individuals

-

Anti-avoidance provisions

4. Taxation and sustainable development

Recommendations called for explicit integration of the Convention with:

-

The SDGs

-

Climate finance needs

-

Gender equality

-

Debt sustainability

-

Human rights obligations

These proposals showed that a fair global tax system is central to financing equitable and sustainable transitions.

Our joint submission: human rights at the center

CESR has consistently submitted detailed recommendations aimed at strengthening the fairness and effectiveness of the convention and aligning it with international human rights law. On this occasion, together with members of the Initiative for Human Rights in Fiscal Policy, we are making the following recommendations:

1. Enforceable and actionable commitments

Our joint submission stresses the need for clear, prescriptive, and enforceable commitments within the Framework Convention itself. Drawing on examples from other framework conventions, we argued that:

-

Core obligations must be established at the level of the Convention

-

Protocols should elaborate further (not replace) obligations

-

Leaving essential commitments to future protocols risks fragmentation and delay

The current draft remains mostly descriptive. Without stronger obligations at the Convention level, implementation may depend almost entirely on additional instruments — a path that risks diluting ambition and widening inequalities.

2. Aligning the convention with international human rights law

Paragraph 9(c) of the ToR requires that tax cooperation be aligned with international human rights law. Our submission explained how this should be operationalized.

Drawing from decades of interpretation by UN human rights mechanisms, we outlined:

-

The interpretive guidance human rights principles provide in assessing tax policies

-

Obligations related to maximum available resources, non-discrimination, and progressive realization.

-

Implications for participation, accountability, and transparency, including public access to tax information.

-

Extraterritorial obligations in connection with tax incentives.

These principles provide a normative framework that can and should guide the Convention text.

Insights from Nairobi: daily reflections

Throughout the two weeks, CESR provided daily updates summarizing key developments. Several themes recurred:

-

Tension between ambition and minimalism: A persistent divide between countries wanting transformative change and those preferring a light, procedural text.

-

Pushback against arbitration: Widespread concern that introducing investor-style dispute mechanisms would jeopardise revenues needed for essential public services.

-

Momentum on taxing high-net-worth individuals: Growing support for addressing extreme wealth concentration through cooperative rules.

-

A stronger African voice: With negotiations held in Nairobi, African States played a central, visible role, bringing new energy and leadership.

-

Recognition that tax is a human rights issue: Several interventions explicitly connected fiscal policy to universal rights, public services, and climate resilience.

These reflections underscored that the Convention has the potential to shift global governance, but also that resistance is strong, particularly from countries, particularly lobbies within those countries, benefiting from the current fragmented system.

Looking ahead

The Nairobi session made one thing clear: the UN Framework Tax Convention could mark a decisive break from decades of exclusionary global tax rulemaking. But this will happen only if States resist pressure to dilute ambition, delay commitments, or outsource critical issues to optional protocols.

As negotiations continue into 2026 and beyond, the key questions remain:

-

Will the Convention redistribute taxing rights more fairly?

-

Will transparency obligations become meaningful?

-

Will dispute resolution protect (rather than undermine) fiscal sovereignty?

-

Will human rights guide the core obligations?

CESR and partners will continue working to ensure that global tax cooperation becomes a driver of equity, resilience, and human dignity — not another mechanism that preserves the status quo.